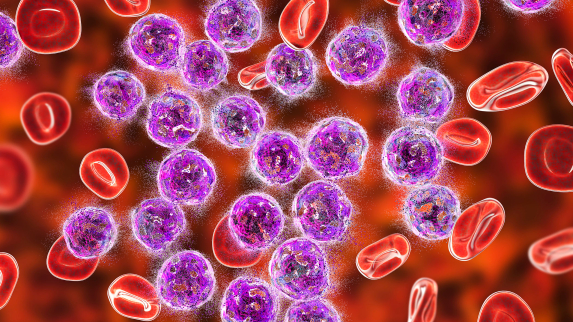

Researchers from Rutgers Health and other institutions have discovered why a powerful leukemia drug eventually fails in most patients – and found a potential way to overcome that resistance. Team members identified a protein that lets cancer cells reshape their energy-producing mitochondria in ways that protect them from venetoclax (brand name, Venclexta), a standard treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that often loses effectiveness after prolonged use. Blocking that protein with experimental compounds in mice with human acute myeloid leukemia restored the drug’s effectiveness and prolonged survival.

The findings, published in Science Advances, reveal an unexpected mechanism of drug resistance and suggest a new approach for one of the deadliest blood cancers in adults.

“We found that mitochondria change their shape to prevent apoptosis, a type of cell suicide induced by these drugs,” said senior study author Christina Glytsou, an assistant professor at Rutgers’ Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy and Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and a member of the Rutgers Cancer Institute’s Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Research Center of Excellence (NJPHORCE). Rutgers Cancer Institute, together with RWJBarnabas Health, is New Jersey’s only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Although venetoclax induces remission in many acute myeloid leukemia patients by triggering cancer cell death, resistance develops in nearly all cases. The five-year survival rate remains at 30% and the disease kills about 11,000 Americans each year.

Using electron microscopy and genetic screens, members of Glytsou’s team discovered that treatment-resistant leukemia cells produce high levels of a protein called OPA1, which controls the internal structure of mitochondria. Cells with these elevated OPA1 levels develop tighter, more numerous folds in their mitochondrial membranes — compartments called cristae – that trap cytochrome c, a molecule that normally triggers cell death when released. To read the full story.